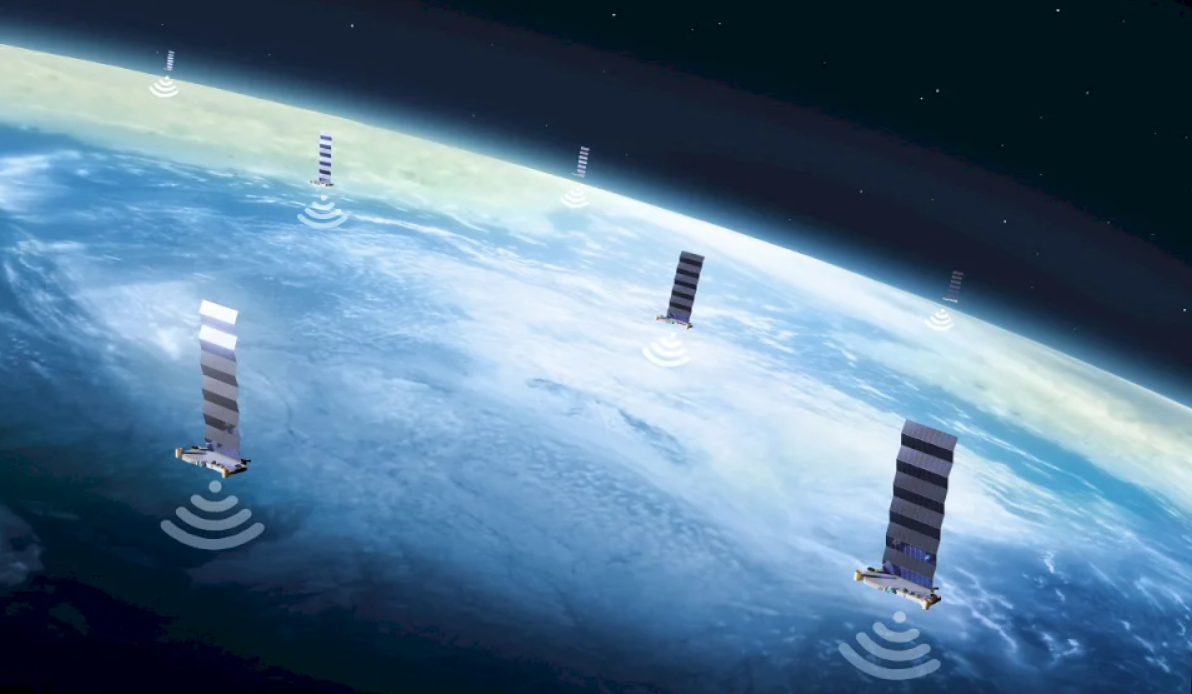

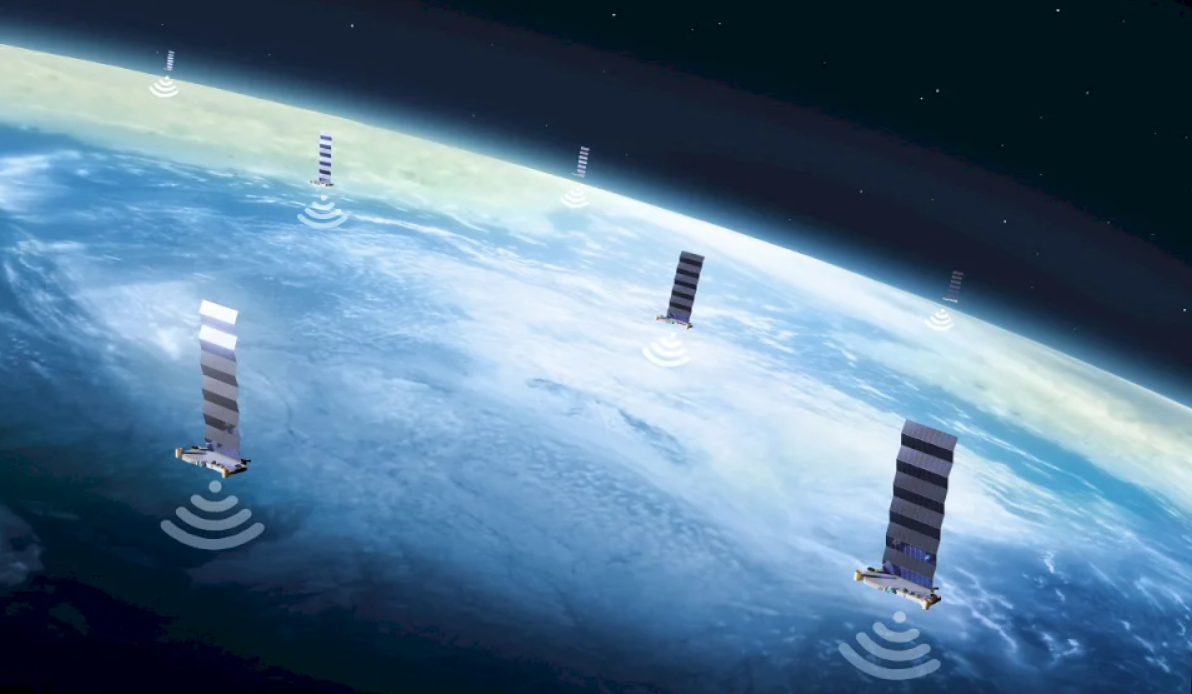

According to astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell from the Smithsonian Institute, approximately one or two Starlink satellites re-enter Earth's atmosphere daily. This situation is expected to worsen as more satellites are launched into Low Earth Orbit (LEO). As of now, over 8,000 Starlink satellites are operational, with SpaceX having launched more than 2,000 since the beginning of the year. Other companies, like Amazon, are also entering the satellite internet race, with plans to deploy over 3,200 satellites.

McDowell projects that with all current and planned projects, there could be around 30,000 satellites in LEO, including those from Starlink, Amazon's Kuiper, and other systems from China. This congestion increases the likelihood of satellite collisions and debris. Starlink satellites have a short lifespan of about five years, after which they are directed to re-enter Earth's atmosphere and burn up upon re-entry.

McDowell projects that with all current and planned projects, there could be around 30,000 satellites in LEO, including those from Starlink, Amazon's Kuiper, and other systems from China. This congestion increases the likelihood of satellite collisions and debris. Starlink satellites have a short lifespan of about five years, after which they are directed to re-enter Earth's atmosphere and burn up upon re-entry.

Scientists are concerned about the pollution caused by these satellites burning up, releasing metal remnants into the stratosphere. A recent study suggests this could trigger a chain reaction, damaging the ozone layer. Additionally, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has warned that by 2035, approximately 28,000 pieces of debris from Starlink satellites could survive re-entry annually, increasing the risk of fatal collisions with people on the ground by 61% each year.

Another potential hazard is the Kessler Syndrome, a catastrophic chain reaction where satellite collisions create more debris, potentially trapping humanity under a debris belt in space. Moreover, during periods of high solar activity, known as solar maximum, a simultaneous failure of many satellites could occur due to solar storms.

Another potential hazard is the Kessler Syndrome, a catastrophic chain reaction where satellite collisions create more debris, potentially trapping humanity under a debris belt in space. Moreover, during periods of high solar activity, known as solar maximum, a simultaneous failure of many satellites could occur due to solar storms.

Elon Musk's ambitious Starlink project aims to provide global internet coverage, but these environmental and safety concerns highlight the complex challenges of large-scale satellite deployment.

Scientists are concerned about the pollution caused by these satellites burning up, releasing metal remnants into the stratosphere. A recent study suggests this could trigger a chain reaction, damaging the ozone layer. Additionally, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has warned that by 2035, approximately 28,000 pieces of debris from Starlink satellites could survive re-entry annually, increasing the risk of fatal collisions with people on the ground by 61% each year.

Elon Musk's ambitious Starlink project aims to provide global internet coverage, but these environmental and safety concerns highlight the complex challenges of large-scale satellite deployment.